CHALLENGE BURGUNDY

March 2019. In 2018 Andrew Jefford, one of our leading wine writers, published an article in ”Decanter” expressing a general disappointment in the wines of Burgundy. He added: “I am in fact a big fan of Burgundies which work; it’s just that the failure rate is much higher than in Bordeaux or Piedmont, and the lustre of the region is such that this [factor] is too often overlooked.” Of bottles he had recently purchased (a number of them from me), he wrote that some of the whites were oxidized while a number of reds were “fair, but didn’t open the door to the magical kingdom of Burgundy bliss.”

March 2019. In 2018 Andrew Jefford, one of our leading wine writers, published an article in ”Decanter” expressing a general disappointment in the wines of Burgundy. He added: “I am in fact a big fan of Burgundies which work; it’s just that the failure rate is much higher than in Bordeaux or Piedmont, and the lustre of the region is such that this [factor] is too often overlooked.” Of bottles he had recently purchased (a number of them from me), he wrote that some of the whites were oxidized while a number of reds were “fair, but didn’t open the door to the magical kingdom of Burgundy bliss.”

He went on to describe how over time a dozen or two other Burgundies, most from highly reputed estates, failed to deliver the pleasure one might have expected from such vaunted, and intrinsically expensive, wines.

I took this very much to heart, knowing that many fine Burgundies – including some of the top wines – can disappoint at certain times even when genuinely great (they can be just as closed up and inaccessible at various times as fine claret). So I wrote to him, proposing a friendly debate, a probe, on the whole issue. ”Burgundy is indeed a challenge,” I wrote. “I myself have opened so many bottles of oxidized whites (I’ve poured out many, even including Montrachet itself), and some reds that lack the right level of concentration. Nonetheless, many of the best wines, often far more delicate than claret though just as structured, can be closed up and hard to read for whole periods, sometimes years, and only show their full majesty at particular moments…

“So what about a “Challenge Burgundy” tasting hosted here in the UK?” I wrote, “with me trying to pick out a range of wines that would really show the region at its best? And with you writing exactly what you think?”

Andrew, being the man he is, rose to the challenge. To cut the story short, it was decided that Andrew would travel to England from his base in the south of France and that the tasting, strictly blind, would be held at my home in Kent in December 2018.

He duly arrived on December 8th, when we were joined by a friend of mine, Duncan Richford, a true oenophile and a great collector of fine wines (his collection is heavily dominated by the wines of Burgundy). He brought along three magnificent bottles: 2007 Meursault 1er Cru Perrières and 1990 Volnay 1er Cru Santenots du Milieu (both from Domaine Comte Lafon), and 1993 Clos de la Roche (Domaine Hubert Lignier). This trio filled in some of the holes in my own collection, which is by no means comprehensive. Fifteen other Burgundies wines were supplied by me. No free samples were requested or supplied.

In January 2019 Andrew published his resultant article on that tasting, “Challenge Burgundy”, in the online “Decanter Premium”. In a preamble, he points out that “critics reach most of their conclusions on the basis of tasting, not on drinking. This process is the best we have, but it is comprehensively flawed – hence the importance of blind tasting of bottled wines… Even then, no mass assessment can ever overcome the lack of essential drinking scrutiny every wine needs.”

The tasting’s eighteen wines spanned no fewer than thirteen vintages, from 2015 to 1983, with Andrew and Duncan tasting every one of them blind.

When planning the event I’d given a lot of thought to Andrew’s point about the need actually to DRINK wines in order to understand them fully. It was clearly of the first importance that the wines should first be tasted blind to ensure that they would be judged and evaluated solely on the basis of their intrinsic quality.

On the art of writing, Hemingway said that you must write first in hot blood and then correct in cold blood. With wine-tasting it’s the exact opposite.

To capture the true essence of any wine, judging it with complete objectivity, you must first taste in cold blood, looking at every single aspect: Colour, aroma, initial taste, middle palate, acidity, tannin, texture, aftertaste, finish, and overall balance. You must, of course, take careful note of its pleasure-giving side too, while refusing at that stage to be swayed by its charm.

Only then, having probed the wine’s depths to the limit, can you allow yourself to retaste it in hot blood. In doing so, you can now fully respond to its sensuous, hedonistic side as well as its formalistic aspects; and only now can you experience the wine fully, as an integrated whole, a fusion of both cerebral and sensual qualities.

That’s why that second tasting, with full disclosure of a wine’s identity, is the perfect complement to a blind tasting; for it provides the “essential drinking scrutiny”, the ability to swallow a wine and follow flavour and aftertaste to the very end, that Andrew sets such store by – as do all serious tasters.

To this end I arranged a small post-tasting dinner for ten Burgundophiles: Andrew, Duncan, and myself; my wife Lisbet; and six other wine-loving friends. The venue: the excellent Fordwich Arms near Canterbury. The restaurant’s elegant, tapas-sized dishes were ideally suited to bring out and enhance the innate excellence of that sequence of fine whites and reds from Burgundy’s Côte d’Or.

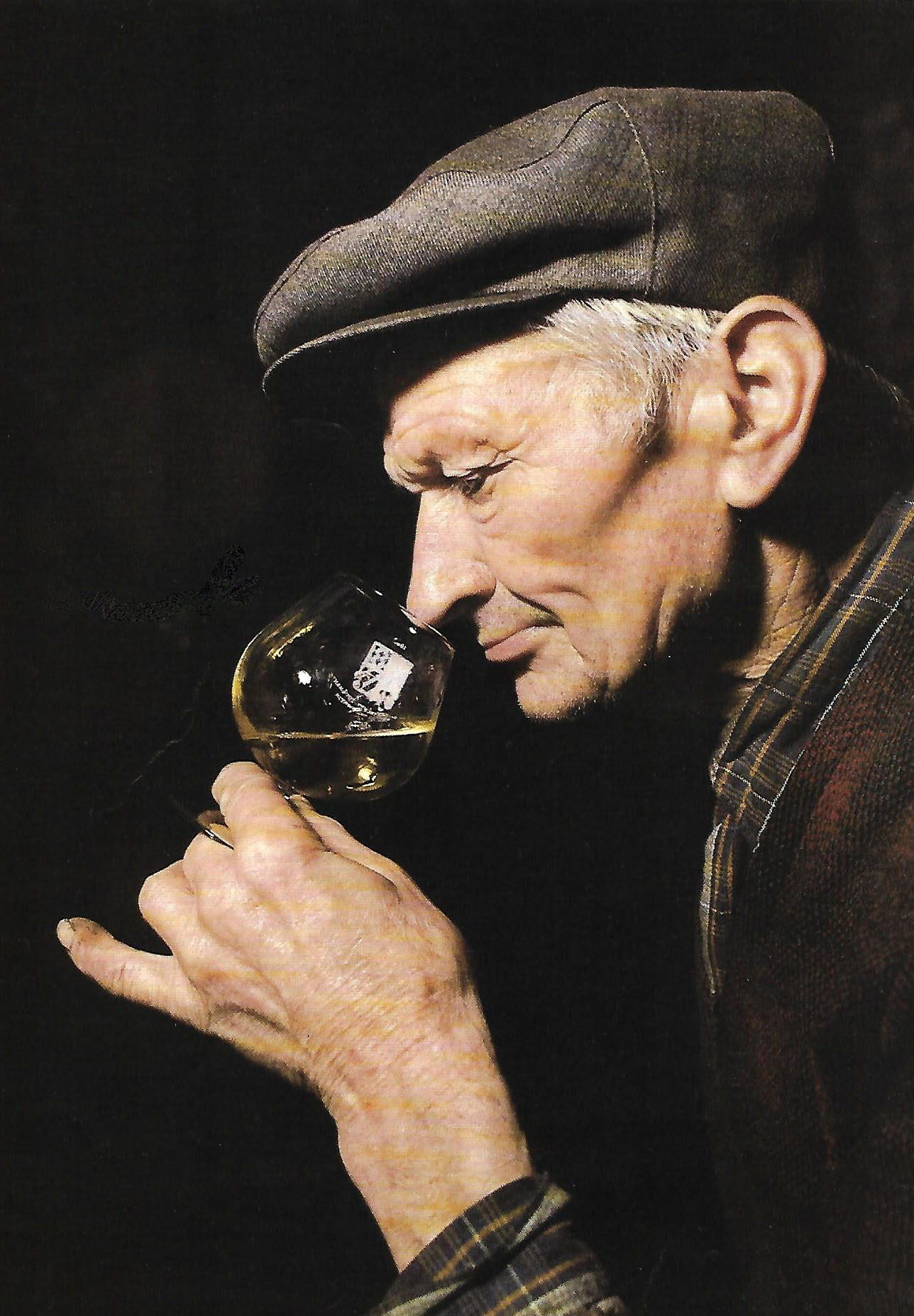

Andrew Jefford savours a great white Burgundy. Could it be Corton Charlemagne or Chevalier Montrachet?

In his article, Andrew had only space for tasting notes on 10 of the 18 wines; but in his introduction he also delivered a thumbnail sketch of two of the remaining eight. The first of these was Etienne Sauzet’s “excellent and impressive 2015 Puligny-Montrachet, a warm and nourishing… village wine of great poise and balance which I was convinced had to be a Premier Cru.” The second: “Even better was a much older village-level 1993 Puligny-Montrachet from Leflaive which I also considered to be at the very least Premier Cru level.”

Of the ten wines on which he wrote detailed tasting notes, three earned 96 points:

1983 Chambertin (Domaine Rousseau), 2003 Corton Charlemagne in magnum (Domaine Rapet), and 2005 Clos Saint Denis (Domaine Dujac).

Three more were accorded 95 points: 2011 Chevalier-Montrachet (Etienne Sauzet), 1999 Nuits Saint Georges 1er Cru Clos des Porrets (Domaine Gouges), and 2001 Musigny Vieilles Vignes, Grand Cru (Domaine Comte Georges de Vogüé).

Of the rest, 1991 Bienvenues-Bâtard-Montrachet (Domaine Leflaive) was awarded 94 points, Lafon’s 2007 Meursault 1er Cru Perrières 93 points; and Dujac’s 2012 Morey Saint Denis 1er Cru Monts Luisants Blanc 92 points. A “simple” 2015 Bourgogne Rouge from Domaine Tollot-Beaut was awarded 89 points – a notably high score for a generic red Burgundy.

Of bottles not included in Andrew’s list, I greatly appreciated Duncan Richford’s splendid 1990 Volnay Santenots du Milieu and his equally wonderful 1993 Clos de la Roche from Hubert Lignier. Also first-rate was a magnum of 1999 Pommard 1er Cru Grand Clos des Epenots (de Courcel). An ’03 Corton Bressandes from Tollot-Beaut, however, was still closed up and still overly tannic; while my last bottle of 1989 Volnay Clos des Ducs (Marquis d’Angerville) was frankly a letdown. While all previous bottles had been simply glorious this one was over the top.

A special word on Rousseau’s 1983 Chambertin. That vintage was a problematic one. It was so freakishly hot that year that much of the fruit all over Burgundy rapidly became overripe, developing “farmyardy” flavours. The berries were often tiny and raisiny, with very little juice. Most wines, when very young, did not show well, being on the heavy side and lacking freshness.

Charles Rousseau, tasting the ‘83s with me long ago, in 1984, acknowledged that they lacked charm but assured me that they would develop splendidly in the longer term. “I remember wines like these that my father made. They always turned out well.”

Nonetheless, his ‘83s remained unalluring for year after year. And year after year Monsieur Rousseau continued to predict future greatness. At home I tasted a bottle or two at yearly intervals; but after more than two decades I was still unable to register any real improvement and began to give up hope.

Then, some 18 months ago, all hopes were redeemed when, with some trepidation, I uncorked my last bottle of 1983 Gevrey Clos Saint Jacques. Miraculously, it had shed its thick, raisiny taste and smelled as pure as spring water, delivering glorious, silky Pinot Noir fruit on an extremely prolonged aftertaste. A great bottle. And a kind of vinous miracle.

I therefore resolved to keep my last bottle of Rousseau’s ’83 Chambertin a while longer. This was very fortunate, as that meant it was still available for inclusion in the Challenge Burgundy tasting. Pale but lustrous, it had a sublime, soaring bouquet of wild strawberry and raspberry meshed with oriental spices, and a profound Pinot Noir flavour of great complexity and extreme finesse. The aftertaste was phenomenally long. A truly great wine – and well worth the 35-year wait!

Those who wish to read Andrew’s article can find it in the January 2019 issue “Decanter Premium” at: Jefford : Challenge Burgundy (subscription required).

Photos by Liz Mott

© Frank Ward 2019

CHALLENGE BURGUNDY « Oeno-File, the Wine & Gastronomy Column said

[…] * CHALLENGE BURGUNDY […]