FOUR NIGHTS IN MARSEILLE

February 2020. Writing in the 1830s, Stendhal declared that “If Bordeaux is the most beautiful city in France, Marseille is the prettiest.” Were he still alive, he would surely have to revise his opinion somewhat were he to visit Marseille in the present day, though it’s still a great city and well worth a special journey.

February 2020. Writing in the 1830s, Stendhal declared that “If Bordeaux is the most beautiful city in France, Marseille is the prettiest.” Were he still alive, he would surely have to revise his opinion somewhat were he to visit Marseille in the present day, though it’s still a great city and well worth a special journey.

Why so? The main reason is that in January 1943 the Germans, aided by the French police, dynamited much of the city’s historic old town and demolished the gigantic Marseille transporter bridge, which had been regarded as the city’s equivalent to the Eiffel Tower in Paris. By the end of World War Two the beautiful Old Port was left in complete ruins.

Today, despite that grievous damage, the port can still boast one of the most magnificent locations of its kind in the world. Sadly though, the handsome old buildings of the past have been replaced by anonymous blocks of flats that now line the horseshoe-shaped port. But it remains the vital, living centre of the city, berthed with hosts of yachts, small craft, and ferries and, on shore, populated by a constant stream of human beings from all over the world. At pavement level there are dozens of restaurants, bistros, and cafes of every conceivable style.

In short, Marseille still has a certain grandeur.

All the same, when I arrived, not long ago, I asked myself if I’d possibly made a big mistake. I’d already been to Marseille four times and it struck me that I’d surely seen everything it had to offer. In addition, it being late autumn, almost all of the city’s museums and art galleries were closed for renovation. We walked several kilometres to one of them, urged to do so by somebody at the hotel, only to find that it was closed for the season. And the first meal – in the Michelin-starred l’Epuisette, beautifully sited on the edge of the bay – was “correct” but lustreless. Their fish-and-shellfish menu simply lacked inspiration. I found two excellent wines on their list, however; a finely-crafted if immature Saint Joseph Blanc from Gripa and a wondrous 2008 Vacqueyras from Château des Tours (the owners of Rayas).

Then a post-dinner happening that should have been catastrophic but which somehow energized us (myself and an old friend John): a torrential downpour, with flashes of lightning and explosions of thunder that looked and sounded like the end of the world. The rain – almost a monsoon – forced us to seek shelter in a shop doorway and we were pinned down there for a good hour, prisoners of the God Thor. But such excitement was generated by that constant lightning and bead-curtain downpours that we were stimulated by the sheer drama rather than enervated. We returned to our respective rooms feeling livelier than when we’d set out.

The next day, though it was well into October, was like summer at its best: crystalline light, lots of sunshine, and a pleasant light breeze. We were quick to grasp that there was a lot more to see in Marseille than we’d imagined: a vital Arabic market, a whole series of quarters each with its own character, a fleet of small ships offering trips along the coast, and a lively populace, many of whom had what Stendhal called “the Greek features of the people of Marseille”.

On the city’s climate he went on to remark: “I cannot say enough good about the climate and the physical conditions of life here; but if the mistral blows you will curse Marseille and only think of leaving it.” In fact, the mistral blew during one whole day during our sojourn, and after only one hour of that withering onslaught, we both began to understand what Stendhal meant! It made one grasp how such winds, at high altitudes, can throw a 300-ton airliner about like a ping-pong ball. At ground level, it can literally blow people off their feet while casting dust and other debris into their eyes. When prolonged, it can plunge its victims into deep depression. Luckily for us it subsided after a few hours.

Gastronomically, our luck soon turned, for two of the finest meals of my life awaited us. In addition, our hotel, the Intercontinental Hôtel Dieu, was superbly located, standing atop a hill and only minutes away on foot from the port, which it overlooked, and affording splendid views. The rooms were elegant and spacious, the weather perfect.

And the one museum that was still open, Mucem, was so full of good things that we were able to spend several enjoyable hours there. The place is made up of three separate complexes, the main one being housed in a gigantic fortress, Fort Saint Jean, which dates from the 12th century and houses no fewer than one million art works, objects of one sort or another, and multifarious documents. A central theme is European and Mediterranean civilization.

The Michelin Guide – still the most reliable judge of restaurants – states that a restaurant called Madame Jeanne had an exceptionally good wine list. So I booked a table there. On arrival, at 20.30, we found the place deserted. A perusal of the wine list showed that almost all the wines were no more than one or two years old so I politely cancelled our booking and landed in another place, only a couple of hundred metres away, called Lauracée. There, we were given a friendly welcome by the youthful owner and we promptly ordered their 44 Euro menu. This comprised tasty carpaccio of raw tuna, followed by stewed jarret of milk-fed veal. When I saw the latter on the menu I asked if the veal was “sous la mère?”, a term used to describe the highest quality of veal, one only fed on its own mother’s milk. The young man looked surprised. “Not many people know about that distinction,” he said.

(The other two categories of true veal, in descending order of quality, are (a) that fed on fresh cow’s milk but not from the calf’s own mother; and (b) fed on dried cow’s milk – and nothing else.)

For wine, we tried a very good, but overly-youthful, 2017 Chablis from Billaud-Salmon, and a 2006 Bandol from the great Château Pibarnon estate. Well, in fact we ordered it but never drank it: we didn’t drink it because it had just sold out. “Try this other Bandol instead,” the manager told me. ”In my view it’s even better”. He decanted the wine (usually a good sign, as to a restaurateur’s seriousness). He returned to our table twenty minutes later. “How is it?” he asked, noting, a bit nervously, that little had been drunk.

“Sad to say, harsh, even brutal, with coarse tannins and unripe fruit,” I replied. He grimaced and went away. Ten minutes later he returned. “You don’t have to drink that. The bottle’s on me.”

I chose instead an old-vine bottle of a 2011 Julienas, one of Beaujolais’ best crus. Excellent. What a relief! It’s horrible sitting in a restaurant where, as often happens, the staff simply refuse to cancel your order when a wine proves to be defective – or agree with you that the wine’s no good but charge for it anyway! I was impressed by that young restaurateur’s humane attitude: so many of his colleagues go to extraordinary lengths to avoid replacing defective bottles.

The best meal of the trip – and one of the finest meals of my life – was taken at the three-star Petit Nice, an elegant restaurant nestling on a rocky promontory overlooking the Mediterranean. The food was so delectable I’m quite unable to give a detailed description of it (though I’ll try). At the first mouthful I nearly slid under the table, succumbing to astonishment and delight, at the food’s sheer excellence. Each of the eight or so tapas-sized seafood dishes was so exquisite – without the tiniest hint of pretentiousness – that I suspended all analytical thought, while registering the food’s technical perfection, and giving way to sheer abandon. I did, though, have the presence of mind to note down the composition of one item: a sublime puree of cauliflower infused with “petals” of dried red mullet and sea bream with miniature fragments of crisp-fried fish skin. That may sound complicated but it was utterly delicious and as light as a feather.

In writing, I remember a bit more:

The first item of all was what they called “avant-goût”. What looked like tiny pieces of Fabergé jewellery were weightless and contained more flavour than many a whole five-course meal. “Trois poissons” rang all the changes on three of the Med’s finest fish; and was followed by “les poissons du sud en caravane nordique” then “relief de pêche et voile de seche”.

All this while sitting looking out over the luminescent Mediterranean, the colour of ameythyst, bathed in bright sunshine, while drinking a glorious bottle of 2015 Condrieu “Coteau du Chéry” from André Perret. Towards the end, a glass of almost lecherously inviting 2010 Hermitage Petite Chapelle from Jaboulet accompanied the last dish or two – the wine’s richness in no way cancelling out the food’s delicacy.

It’s not often one can sit back and experience such pure bliss – a fusion of great and inventive cooking, lovely ambience, a beautiful view, and superb wine – for over three hours.

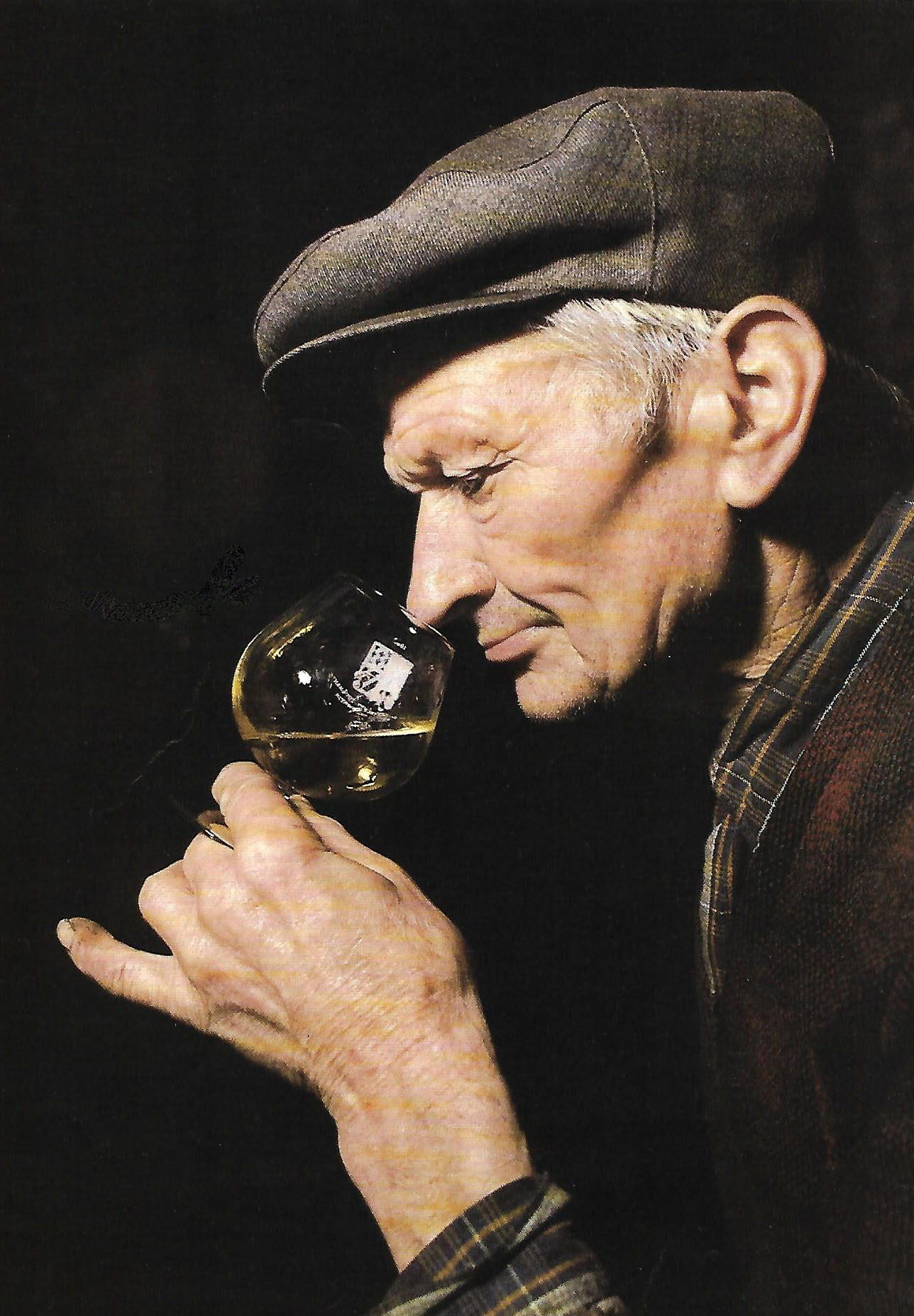

Marseille is close to several wine regions, one of which is Bandol. Because of its propinquity we dropped in on one that regions’s top properties, Château Pibarnon, that same wine estate whose wine we’d attempted to order a couple of days earlier. The proprietors were absent so we had a fairly simple, though instructive, tasting.

A 2018 Rosé – they make 70,000 or so bottles a year – was pinkish, with a slight orange tinge, and smelled like cloudberry and strawberry, its amenable flavour given extra depth by a touch of bitterness. The 2019 that followed was fuller and weightier, with a suggestion of orange peel, but was still rather closed. Tasting the third Rosé, the 2016, revealed something that should be tattooed on the palms of all sommeliers: Three years of age isn’t a great age for a rosé but those extra years had transformed the wine into something altogether more interesting. Fragrant and round, it smelled like a meld of cloudberry, saffron, and strawberry and had a properly vinous flavour with some genuine depth.

A 2018 Rosé – they make 70,000 or so bottles a year – was pinkish, with a slight orange tinge, and smelled like cloudberry and strawberry, its amenable flavour given extra depth by a touch of bitterness. The 2019 that followed was fuller and weightier, with a suggestion of orange peel, but was still rather closed. Tasting the third Rosé, the 2016, revealed something that should be tattooed on the palms of all sommeliers: Three years of age isn’t a great age for a rosé but those extra years had transformed the wine into something altogether more interesting. Fragrant and round, it smelled like a meld of cloudberry, saffron, and strawberry and had a properly vinous flavour with some genuine depth.

2015 CHÂTEAU PIBARNON ROUGE

Well-coloured, this had an elegant scent suggestive of damson, blackcurrant, and dark chocolate. The flavour is smooth, even suave, yet also slightly gritty (from the tannins). The flavour is focused and well balanced, but it clearly needs a good 6-7 years to become accessible, with a further dozen or so to bring about full maturity.

2014 CHÂTEAU PIBARNON ROUGE

The colour, similarly dark, is more evolved, and so too is the aroma, which suggests smoke, elderberry, blackberry, and soot. The Grenache can be picked out for its voluptuous, spicy character, I also detect a touch of blackcurrant and underbrush. The flavour is rich and intense, soon expanding to include liquorice. The aftertaste has plenty of sweep, with pronounced Bandol character (richness, intensity, and depth). A forceful wine, with incipient subtlety, which will be splendid with game 2025-40.

2008 CHÂTEAU PIBARNON ROUGE

A dark wine smelling like damson and carnation with suggestions of graphite and red rose petals. Unfortunately the wine was a bit oxidized – the sample must have been open for several days.

Yet – as I know from experience – the vast majority of restaurants, including many with Michelin stars, are presently serving the youngest of those three vintages, usually 2017 or even 2018, 1-2 years before they begin to develop any real character. Almost any wine of character needs 12-36 months in the bottle to develop into something delicious, its scent and flavour tripled thereby, and starting to unveil secondary, even tertiary, aromas – those core scents that reveal the true nature of any wine fit to be assessed seriously.

The other outstanding meal – our last dinner in the city – was at Une Table au Sud, a first-floor place with a wonderful view over the Old Port. Their Marseille Menu, at 105 Euros, is almost wholly devoted to fish and shellfish, every item of which was as fresh as could be. One major feature was ”Ma Version de l’Aioli”, a positively aerial dish made up of fresh and dried cod, raw vegetables, with olive oil and lime juice. It was as much a pleasure to the eye as to the palate.

© Frank Ward 2020

Photos : John Statham