MEMORIES OF CHARLES ROUSSEAU

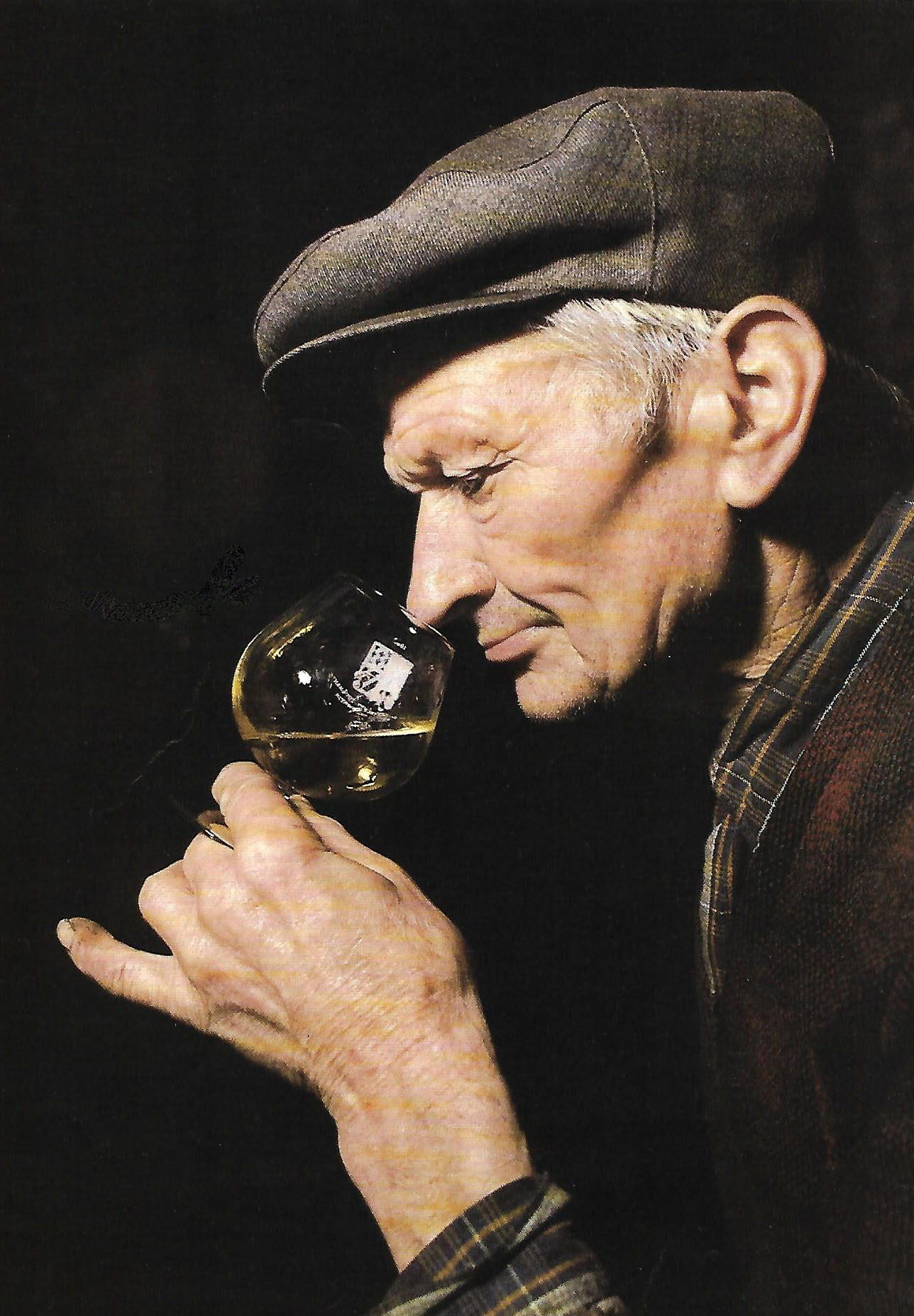

June 2016. I felt a real pang when I heard of the recent death of Charles Rousseau, of Domaine Armand Rousseau, at the age of 93. He was not just a great vigneron and wine-maker, he was also a man of exceptional warmth and humanity. I’d known him for more than 35 years.

June 2016. I felt a real pang when I heard of the recent death of Charles Rousseau, of Domaine Armand Rousseau, at the age of 93. He was not just a great vigneron and wine-maker, he was also a man of exceptional warmth and humanity. I’d known him for more than 35 years.

a

a

When I first met Charles Rousseau in the early 1980s, he gave me a splendid tasting of the Domaine’s wines (in the underrated 1980 vintage – excellent in the Côte de Nuits as well as in the Rhône). When I was about to leave, noting my love of Burgundy wines, he took a piece of paper, drew a simple map of the village of Gevrey-Chambertin, and marked the names of all the other major Chambertin proprietors, indicating where they were located. “Voilà, la route du Chambertin!” he said with a smile.

a

a

In due course, when still a young freelance artist, I became Domaine Rousseau’s sole agent in Sweden, where I then happened to live (a long story I’ll tell elsewhere), a position I held for over thirty years. Amazingly, it took a half-decade of unremitting effort to get Rousseau wines listed by the bureaucratic Swedish monopoly; but thereafter they purchased the wines – mostly Chambertin – in almost every vintage. In those far-off days demand for Burgundy was nowhere as strong as it is today. As a result, I was often able to persuade the Domaine to offer Sweden thirty 12-bottle cases (360 bottles), sometimes even fifty (600 bottles), of Rousseau Chambertin.

a

a

He was always there to greet me when I paid my annual visit to the Domaine. First, we’d sit together in his tiny office and he’d give me a vivid description of the latest vintage (the one we were about to sample), recounting any problems that might have arisen in the process and pinpointing its chief strengths and weaknesses.

a

a

More recently, when in old age he’d ceased to accompany me down to the cellar (a job he handed over to Frédéric Robert, now in overall charge of the cellars) he expressed serious concerns about the future of great Burgundy, in the light of ever-mounting temperatures at harvest times. “The day may come,” he said darkly, “when we’ll have to uproot the Pinot Noir and plant Merlot in its place!” I’m still not sure how serious he was – though I am certain that he felt certain disquiet – after all, he had over 60 years’ experience to draw on.

a

a

Both of us loved good food and, following that preamble, we’d then spend a good 10-15 minutes discussing the merits and demerits of this or that restaurant, whether local or from farther afield. In this respect, Charles Rousseau had a truly nationwide appreciation of good French restaurants, many of them far from Burgundy. One place, perhaps, had a chef who truly understood balance and contrast, whose dishes showed true finesse and thereby earned his highest praise; another, formerly great, was no longer as good as in the past, and Rousseau made clear his dissatisfaction; while yet another, a young man on the rise, was showing promise of future greatness, and I, he said, should certainly pay HIM a visit.

a

a

Once, after he and I had tasted together in the cellars, Monsieur Rousseau received a visit from the vice-president of a vast supermarket chain, who’d come to collect a few cases of wine he’d purchased. “Can you recommend a good restaurant for lunch?” the man asked, in a way that subtly suggested that he and his wife would not be averse to eating at Rousseau’s own table. Ignoring the unmistakeable hint, M. Rousseau simply recommended Lameloise, the three-star restaurant in nearby Chagny.

a

Looking slightly miffed, the couple went away, presumably to lunch there.

a

M. Rousseau nodded after them, with a gentle shake of the head. That monsieur, though immeasurably rich, only ever bought the cheapest wines the Domaine had on offer, never the top wines.

a

a

a

a

My wife and I then had the immense pleasure of walking with Charles Rousseau back to his lovely mansion, next to Gevrey-Chambertin’s 13th-century church, for a delicious meal cooked by his wife Jacqueline, and accompanied by an old bottle of Chambertin Clos de Bèze.

a

a

On another occasion M. Rousseau served a Chambertin that had all of the unmistakeable signs of great age. Distinctly brown, but still with a purplish sheen, soft and truffly on the nose, it was still good to drink though clearly in gentle decline. Asked to comment on it, I replied that it was clearly extremely old, and probably a Chambertin. I wasn’t able to hazard a guess as to any particular vintage. “It’s from the First World War,” M. Rousseau told me. “But I don’t know the vintage. The fact is, my father was at the war at the time and it was my mother who had to do the bottling. It’s just that she forgot to put the vintage on the label!”.

a

a

I shall open a bottle of my oldest Rousseau Chambertin in salute to Charles Rousseau, the wine-making Beethoven of Burgundy.

a

a

© Frank Ward 2016

a a