VINCENT LEFLAIVE – Passion & Humanity

February 2019. PORTRAIT. The Chardonnay grape gives fine wines in many parts of the world, but for many it reaches the greatest heights on the Côte de Beaune segment of Burgundy. There, when conditions are ideal, it can achieve complete perfection, with Premiers and Grands cru wines of matchless poise, depth, and finesse. Even “Village” wines can show unexpected depth when from a top estate.

February 2019. PORTRAIT. The Chardonnay grape gives fine wines in many parts of the world, but for many it reaches the greatest heights on the Côte de Beaune segment of Burgundy. There, when conditions are ideal, it can achieve complete perfection, with Premiers and Grands cru wines of matchless poise, depth, and finesse. Even “Village” wines can show unexpected depth when from a top estate.

The biggest and most esteemed source of these lovely white Burgundies is the village of Puligny-Montrachet, a community hemmed in by vineyards too precious to uproot (except for replanting). Within its bounds lie four of Burgundy’s illustrious Grand cru whites (it shares two of them with next door commune Chassagne Montrachet) as well as seventeen superb Premiers crus – a few of which come close to Grand cru quality.

The most celebrated of Puligny’s wine estates is surely that of Domaine Leflaive, which I have visited off and on over the last 40 years. For close on 25 of those years the Domaine was headed by the late Vincent Leflaive, one of the most dedicated, and also one of the most human, of all the hundreds of wine producers I have met in my career as wine taster. I find myself remembering him very often, usually with a smile.

How good are the wines? The magazine “Cuisine et Vins de France” put it very well when they wrote “You do not buy Domaine Leflaive wines; you solicit the honour of being able to exchange money for them”. Clive Coates, writing quite some years ago, got closer to the truth, maintaining that Leflaive wines are “the benchmark by which all white Burgundy must be judged.” The late Marquis d’Angerville, who knew all of vinous Burgundy intimately, once told me: “Leflaive wines epitomize white Burgundy in full majesty. They are perfumed, full of finesse, have great elegance and purity, are long on the palate, and last extremely well.”

(I myself recently opened a 1996 Chevalier Montrachet that I simply cannot banish from my mind.)

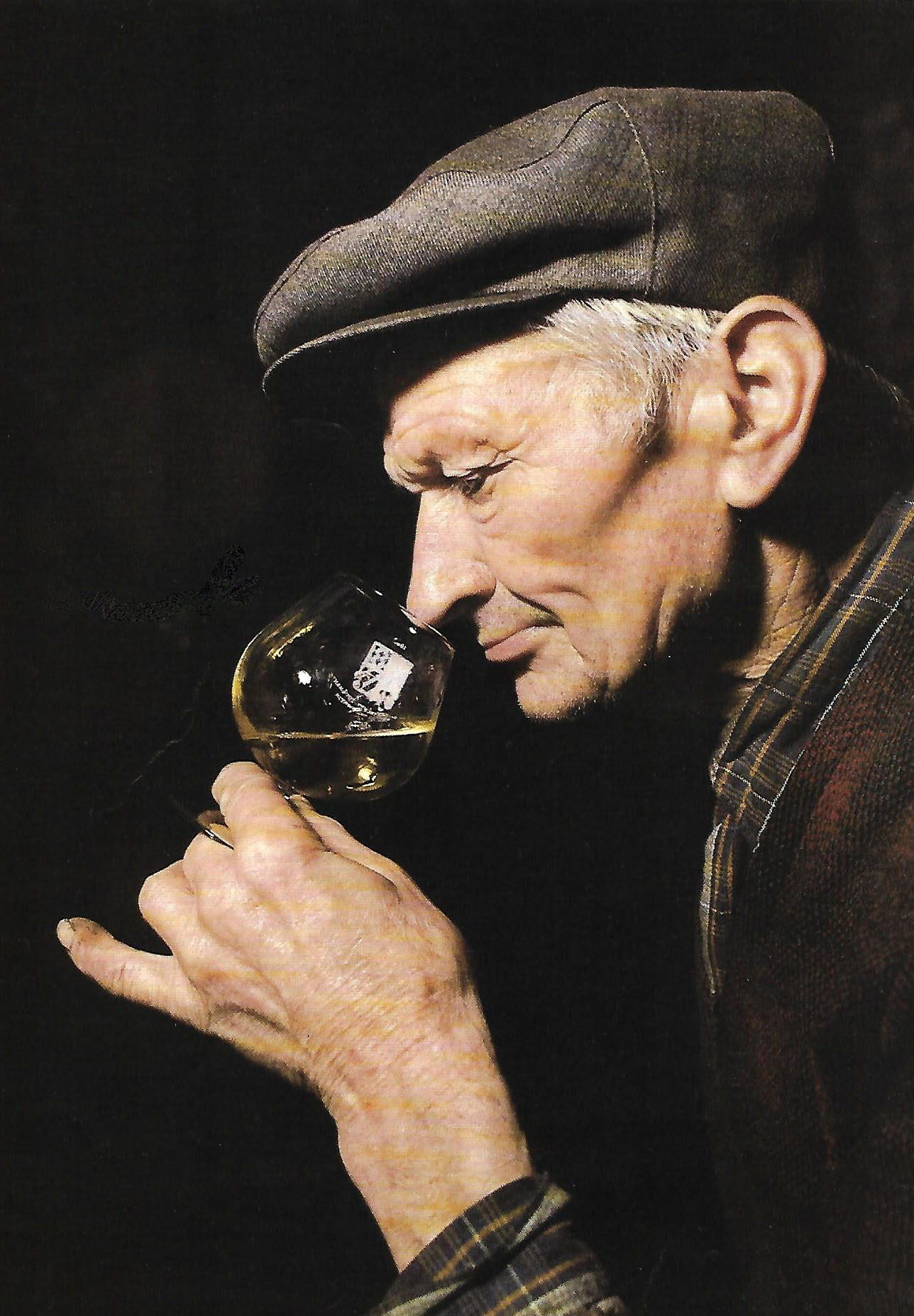

I last saw Vincent Leflaive when he was in his late seventies. His hair was silver, his blue eyes alive with humour and curiosity. His emphatic but sensitive features mirrored his emotions – which he seldom bothered to hide – and his nostrils flared when he was in a peppery mood (not all that infrequently!). He used his powerful, actorish voice to great effect, reducing a room to total silence one moment, filling it with laughter the next.

On my very first visit, in the early 1980s, he met me in the courtyard as I arrived, looking a bit put out. “You’re fifteen minutes late!” he barked at me, with a ferocious look.

I quailed. “Est-ce que c’est grave?” I asked, feeling terrible. “Oui, c’est grave!” he thundered. Then he registered my obvious distress. His expression changed, his innate empathy showing. He gave a warm smile, patted my shoulder, and said, “Non, ce n’est pas grave du tout!”

Over the next twenty or so years we always tasted each new vintage together, while it was still in vat or barrel. When we came to the vat samples, he carried a short step ladder that allowed him to ascend each of the stainless vats in turn, extract a sample with a pipette, and from a height of two metres of so pour a sample first into his own glass (to check the smell), then into mine. Each vat contained wine from one single vineyard (Puligny Village, Puligny Pucelles, Bâtard Montrachet, etc.). We would also try samples from barrels, noting the differences between the two: a Puligny Pucelles from a barrel, for example, with its faint hint of vanillin and slightly yellower colour, would be subtly different from one taken from the inert steel vat.

At bottom a friendly and informal man, Vincent Leflaive liked to wear tweedy jackets and always preferred a cravat to a tie (I only ever saw him wear a tie once, at a formal dinner in Bordeaux). He often eschewed socks, slipping his bare feet into sandals. Yet his innate elegance, his natural poise, never deserted him. If you didn’t know he was a top wine maker you could easily have taken him for a poet or the director of films of great artistic value.

On one later visit, this was in 1988, I found him waiting for me in his light and airy office at the Domaine’s manorial headquarters on the edge of Puligny Montrachet. An empty bottle of 1934 Bâtard Montrachet stood on the stone mantelpiece; Vincent sat at the big oak desk, and after exchanging greetings began telling me about his approach to wine making. This time I was there not just to taste, but also to research an article for an American cultural magazine.

“The Chardonnay doesn’t really benefit from being aged entirely in new oak”, he told me. “The wine loses its freshness and becomes boisé, woody. That’s why only twenty-five percent of our wine goes into new oak casks. The rest is matured in stainless-steel vats or in older casks, which are more or less neutral. If the cuvée looks as if it’s getting too oaky we transfer it into an inert stainless vat.”

In Vincent’s day – he retired in 1990 – Domaine Leflaive owned twenty hectares of vineyard, two thirds of it in priceless Premier Cru and Grand Cru land. The Leflaive family can trace its Burgundian roots as far back as 1580 and has owned vineyards there since 1735. The estate was brought to eminence in modern times by Joseph Leflaive, Vincent’s father, who was in charge from 1905 to 1953. “When my father began building up the domaine, “Vincent told me, “it was almost nothing.”

In fact Joseph Leflaive had inherited a mere two hectares of vineyard when he took over. Demand for wine in those days was weak (for years the Domaine had to sell much of the wine in bulk to negociants – something that would be unthinkable today) and the vineyards were anyway still almost derelict following the phylloxera epidemic of the 1880s. Well into the 1920s prime vineyards were to be had for a song. Joseph bought as much land as he could, bit by bit building the Domaine up to twenty-five hectares. This was vast by Burgundian standards. It includes plots in four Premiers Crus – Combettes, Clavoillon, Folatières, and Pucelles (the latter can command Grand cru prices), as well as in four Grands Crus: Bienvenues-Bâtard-Montrachet, Bâtard-Montrachet, Chevalier-Montrachet, and Montrachet (the latter added as recently as 1991). Their share of Montrachet, the greatest, most complete of all white Burgundies, is a mere 821 square metres. In an average year they only produce a few hundred bottles of this fabled wine.It is even more sought-after than the Montrachet from Domaine de la Romanée Conti.

When Joseph died in 1953, he was succeeded by his two sons, Joseph junior and Vincent. Though they were forced to hold down outside jobs for the next nineteen years, running the Domaine only on weekends, they soon began to see improvements. The first real breakthrough came in 1953, with help coming from the other side of the Atlantic. ”Our then American agents, Frederick Wildman & Sons, stepped in and helped us,” Vincent recalled. “They advanced credit, buying the fifty-threes in advance, and thanks to them we were able to reconstitute the vineyards, buy new equipment, and start restoring the cellars and winery.”

Vincent Leflaive – and his successors, beginning with daughter Anne-Claude – prized loyalty and decency. The steadfast support of those American friends was never forgotten and every year for decades, Wildman received a generous allocation of the wines, which are now in greater worldwide demand than ever.

Leaving the Domaine’s building, we were soon bumping along rutted tracks and over hills to see, with the harvest imminent, how the Chevalier grapes were faring. Vincent surveyed the bunches, declaring that picking needed to be held off to the last possible moment to ensure optimal ripeness. I asked if he had any worries about the vintage. “I am always worried until all the grapes are in,” he said with feeling.

The Chevalier vineyard – this wine is perhaps the subtlest, most refined of all white burgundies – is on a steep slope and is composed mostly of sand and stones. The latter litter the ground, absorbing heat during the day and reflecting it back at night. “In fact it’s easier to pick on this slope than on the flat, as the grapes dangle down into your hand. I once did three weeks of picking.“ His eyes widened comically. “I was exhausted! I ended up on my knees!”

In Burgundy every vineyard gives a subtly different wine, even when only a few metres from its nearest neighbour. Even the ripening grapes taste different from one demarcated plot to the next. The Chevalier grapes were especially small, peeping from beneath the leaves like rare birds’ eggs. Though not quite fully ripe on that day, they were surprisingly sweet, with a flavour of unexpected intensity and a fresh, lingering aftertaste of real distinction. As a grape burst in my mouth, I recognized a taste often found in mature Chevalier-Montrachet – that of tangerine with hints of honey. The juice from this Grand cru grape had a flavour fuller and more complex than that of any of the grapes from Village and Premier Cru vineyards tasted by me on that same day.

Back in the spotless cellars, Vincent was in a joking mood as he pulled corks from the precious bottles we were about to taste. “Bâtard-Montrachet” – plop! – “is a wine for serious people. For company directors, prime ministers, the queen of England. It is a public wine, a wine for banquets. Chevalier” – plop! – “is a wine for drinking with your wife or, if you prefer, with your girlfriend!”

One by one we tasted most of the Domaine’s 1986 and 1985 wines. Each growth showing the same, classic traits. They quickly expanded in the glass, despite their youth, as good wines always do, and we agreed that the 1986s were fairly light but intense, with a long, beautifully precise aftertaste. Vincent favoured the younger vintage, while I preferred the older, richer one. (A magnum of the 1985, given to me by Vincent a few years later, and uncorked after a further twenty years, was unforgettable).

Now the 1987 Chevalier was uncorked. For an “off” vintage one could have expected it to be a letdown, but this was emphatically not the case. Lighter and destined for a shorter life, yes; but it gave off an aroma of exquisite purity and delicacy and had a long, intense aftertaste that was markedly mineral and full of nuances. In fact, while it would surely be outlived by the ’85 and ’86, it would give more pleasure than either over the next few years – at which point the older wines would begin their slow and steady evolution into greatness.

Our tasting, like the poured wines, expanded in scope. Now the legendary 1983 was opened and dispensed. The colour was a glowing yellow-gold with a distinct emerald tint. The nose was slightly smoky and had innumerable aromatic facets, with suggestions of honey and apricot to begin with, then citronella, then white peach, then subtle hints of tropical fruits. The flavour was full, dynamic, concentrated, and of awesome depth. Marine fossils, compressed into the soil of Puligny millions of years ago, left a delicate hint of minerals on the sustained finish.

It was a measure of this wine’s greatness that, despite a high alcohol level (’83 was a very hot vintage) it was neither heavy nor heady, and had great finesse. Still young then, at eight years, it was an uncut diamond of a wine that would, with time, acquire polish and complexity.

Finally the ’79 Chevalier was uncorked. Fully mature, it gave off the most complete aroma of them all, filling one’s nostrils with a soaring tracery of flowery and fruity scents. As the glass was swirled one aroma after another presented itself: apricot, acacia honey, white truffle, greengage, even a fugitive hint of pineapple. The majestic flavour was both unctuous and incisive, showing a delicate ripe-grape sweetness that was a legacy of fruit picked almost a decade earlier. The aftertaste was given “nerve” by a thread of crisp, fresh acidity, which also imparts length.

Vincent Leflaive thrust the corks back into the bottles – we’d be re-tasting them very soon – and placed one or two of them in the hands of our small company, rather as if presenting an award (which in a way he was!). It was time for lunch at Le Montrachet, Puligny’s best restaurant, then the holder of one Michelin star. We strolled across Puligny’s village green, happily laden with bottles, which sparkled in the sun. I found myself wondering what piece of music could possibly do justice to this sequence, or suite rather, of the Domaine’s greatest wines. The “Ode to Joy”? The “Soave Sia Il Vento” trio from Mozart’s “Cosi Fan Tutte”? “The Halleluja Chorus”?

As we entered the restaurant, handing our bottles to the smiling sommelier (who’d soon be tasting them himself prior to pouring them into our glasses) I decided that the best accompaniment was not great music, after all, but the clink of cutlery and glasses and the lively table talk of the man who made the unforgettable wines of Domaine Leflaive.

Vincent Leflaive died in 1993.

Anne-Claude Leflaive died in 2015 aged 59.

© Frank Ward 2019

Vincent LEFLAIVE – Passion & Humanity « Oeno-File, the Wine & Gastronomy Column said

[…] * Vincent Leflaive : Passion & Humanity […]