FOUR DAYS IN LISBON

June 2019. LISBON, capital of Portugal, is a city with many attributes. Built on a series of hills, overlooking the vast expanse of the Tagide estuary, it boasts a number of outstanding museums (most notably the Gulbenkian), many magical squares and alleys, and – perhaps most of all – a people who are open, helpful, gentle, and welcoming. Their infinitely poignant song, fado, heart-rendingly tender, seems to sum up something in the Portuguese character…

June 2019. LISBON, capital of Portugal, is a city with many attributes. Built on a series of hills, overlooking the vast expanse of the Tagide estuary, it boasts a number of outstanding museums (most notably the Gulbenkian), many magical squares and alleys, and – perhaps most of all – a people who are open, helpful, gentle, and welcoming. Their infinitely poignant song, fado, heart-rendingly tender, seems to sum up something in the Portuguese character…

With many switchbacking streets, some of them on different levels and not immediately accessible (and often devilishly hard to find!) it’s a city where it’s easy to get lost. But that’s no problem. All you have to do is enter a shop – a jewellers, a laundry, a cafe, a tailor’s – and somebody will leave their station, join you on the pavement, and point you in the right direction, while giving exact verbal instructions (in English) on how to reach your destination. It’s a very personal, intimate city.

This was not my first visit. Some 25 years ago I spent a few days there on my own. During my stay I discovered a charming, very simple restaurant that used to do a delicious grilled sole. I went there almost every day for lunch. What struck me particularly – apart from the honest cooking and the modest prices – was the fact that they had a wash-basin inside the actual dining room – a boon when you’re using your fingers on shellfish or oysters. I wasn’t able to find it this time but anyway had a series of good honest meals and one outstanding one.

This was not my first visit. Some 25 years ago I spent a few days there on my own. During my stay I discovered a charming, very simple restaurant that used to do a delicious grilled sole. I went there almost every day for lunch. What struck me particularly – apart from the honest cooking and the modest prices – was the fact that they had a wash-basin inside the actual dining room – a boon when you’re using your fingers on shellfish or oysters. I wasn’t able to find it this time but anyway had a series of good honest meals and one outstanding one.

That was at a place called Belcanto, the first Portuguse restaurant ever to be awarded two Michelin stars. Strange to say, I can’t describe the dining room. Why? Not due to a temporary loss of vision or amnesia, but because I, and a food-loving friend, were immediately whisked into the kitchen, where we were soon ensconced at the Chef’s table, whose two-metre-long surface was soon decorated with the first of no fewer than 16 culinary creations devised by master chef Jose Avillez, a slim and striking young man who looks as if he could easily make a soufflé while driving a racing car and writing a poem at the same time!

He declares “the spirit of overcoming that has always defined the Portuguese people is what this menu is all about. Because we are never satisfied with what exists; because we like to risk and reinvent, with insight and enthusiasm. We’ve taken another look at some of our most emblematic dishes and we’ve reinvented them…We’ve merged innovation with tradition, bringing forth new flavours, new textures, new concepts, new sensations.”

These ringing words remind one that Portugal is a nation of navigators and explorers – think Magellan, who gave the Pacific Ocean its name and whose ship was the first to circumnavigate the world. Think Portugal’s King Ferdinand and Queen Isabella who empowered Christopher Columbus to make his daring voyages across unknown seas, leading to his discovery of the Americas and much else.

In no time Sommelier Nadia Desiderio extracted the cork of 1985 white Dao and poured its amber contents into our glasses, so that we barely had time to analyse the first dish, “Dirty elderini with spherical olive” (El Bulli 2005), while registering that it was delicious. Then the second of those 16 dishes was placed before us with a flourish by Maître d’hôtel Luis Reis: Cod and chickpea “stones” which looked very like the kind of pebbles you find on a beach but which were, in fact, eminently chewable as well as being sapid. A playful item that entertained the palate.

Next, Azorean tuna “bouquet””, a tiny feather-light cornet encasing a blend of seaweed and tuna. Then a third variation on the sea: cured red mullet, flecked with seaweed, with trout roe and pumpkin-seed puree. Then another variation on the marine theme: Razor clams with shavings of lupin bean ice, given extra intensity by a blob of sea urchin and green peach. Now another wave from the ocean: Lobster with haricots blancs, marrow, and caviar. The lobster, almost raw, had that special delicacy only found in cool waters. In complete contrast was an intensely flavoured dish centering on the unique scarlet Algarve prawn – the size of a langoustine – done in two ways. First, in maize “porridge”, then with the head in a crust of beetroot salt, moistened with a wondrous sauce, the very essence of shellfish at its very best.

Around this time, at about the tenth dish, featuring many scores of ingredients, I found myself experiencing a kind of palate fatigue. England’s highly respected cook Prue Leith has interesting things to say about this phenomenon. “By and large, a plate of food should not have more than four or five flavours in it. If you use too many flavours your tastebuds cannot cope.” What she favours, she adds, are flavours that are crisp and individual, clean-cut and fresh.

Luckily a kind of gastronomic second wind came along at this point and, tastebuds at the ready, I was once more into the fray.

Roasted cozido – Portuguese pot au feu with cabbage – came next, followed by “LT yok with a puree of sun root, a farinheira of roe, and cabidela sauce”. This was followed by sea bass with smoked avocado with pistachio oil, lime zest, and dashi. The one and only meat dish was smoked roast squab with foie gras, thin crust pie, black chanterelles, and a sauce compounded of hazelnut and cinnamon. Two cheeses, both young but tasty, brought a welcome change of tempo.

And now one of the most original – and intriguing – dishes of all 16.

And it was a dessert.

Its service was shrouded in mystery. It would be “very dark”, we were told, darkly. “Chocolate, surely!” I ventured. I received a non-commital grin and shake of head in reply. “Ah,” I thought, though without any conclusion.

The mystery dessert was dark and glistening. It was a dense in flavour but, while there was more than a hint of chocolate in it, that was definitely not the dominant flavour. Or texture. I took a spoonful of the liquid. Hmm. “It looks like chocolate, yes; but only up to a point,” I began. “It tastes partly of chocolate too. But there’s something else… It doesn’t have the slight grittiness of chocolate nor any of its bitterness. In fact it’s velvety as to texture. In addition, it’s far darker than chocolate can ever be, almost black. The only one comestible in the entire pantheon of the world’s eatables that is as black as this is – squid ink! “

(In fact it was cuttlefish ink, but close enough!).

* * * *

A week or so before I left for Lisbon I found a bottle of an old Portuguese wine in my cellar: 1970 Colares Chitas. It had been given to me some 25 years ago by its producer, Antonio Bernardino Paolo de Silva. This occurred when I’d made a beeline for his winery after having learned that his vines – as were all wines in the Colares Chitas appellation – were ungrafted. They were safe from grafting due to the special properties of Colares’s sandy soil, in which the phylloxera could not establish itself.

I examined the bottle, which I’d forgotten about. I now recalled that it had been a good twenty years old when it was handed to me a quarter of a century ago. Now it was now close to a half-century. Level, well into neck. The colour gave off scarlet flashes when the bottle was held against a bright light. It was as limpid and lustrous as a ruby in a spotlight. What a good idea it would be to taste it before leaving for Lisbon! Out came the cork. Because of its rich colour, high viscosity, and intense aroma I decanted it.

It seemed overly tannic to begin with, but that seeming intransigence abated in no time at all. Before my very eyes, beneath my very nose, it morphed into a truly bewitching potion:

1970 COLARES CHITAS VINHAS VELHAS

At 49 years, this has a solid, glowing plum-purple colour, not unlike that of a top Barolo, with a gingery purple rim. The bouquet is a fascinating, spicy amalgam of aromas, with suggestions of plum jam, ginger, cinnamon, and camphor. Within minutes hints of chocolate enter into the picture, as well as something ferrous. It gains in deliciousness by the minute, rounding out in the glass, turning increasingly sumptuous, with a uniquely Portugese vitality – think Douro – having a certain affinity with that great Douro red, Barca Velha. But there’s also a special complexity, of unique terroir, that gives it an affinity with a fine Gevrey Chambertin ( Latricières Chambertin, with its sinewy structure). A wonderful bottle.

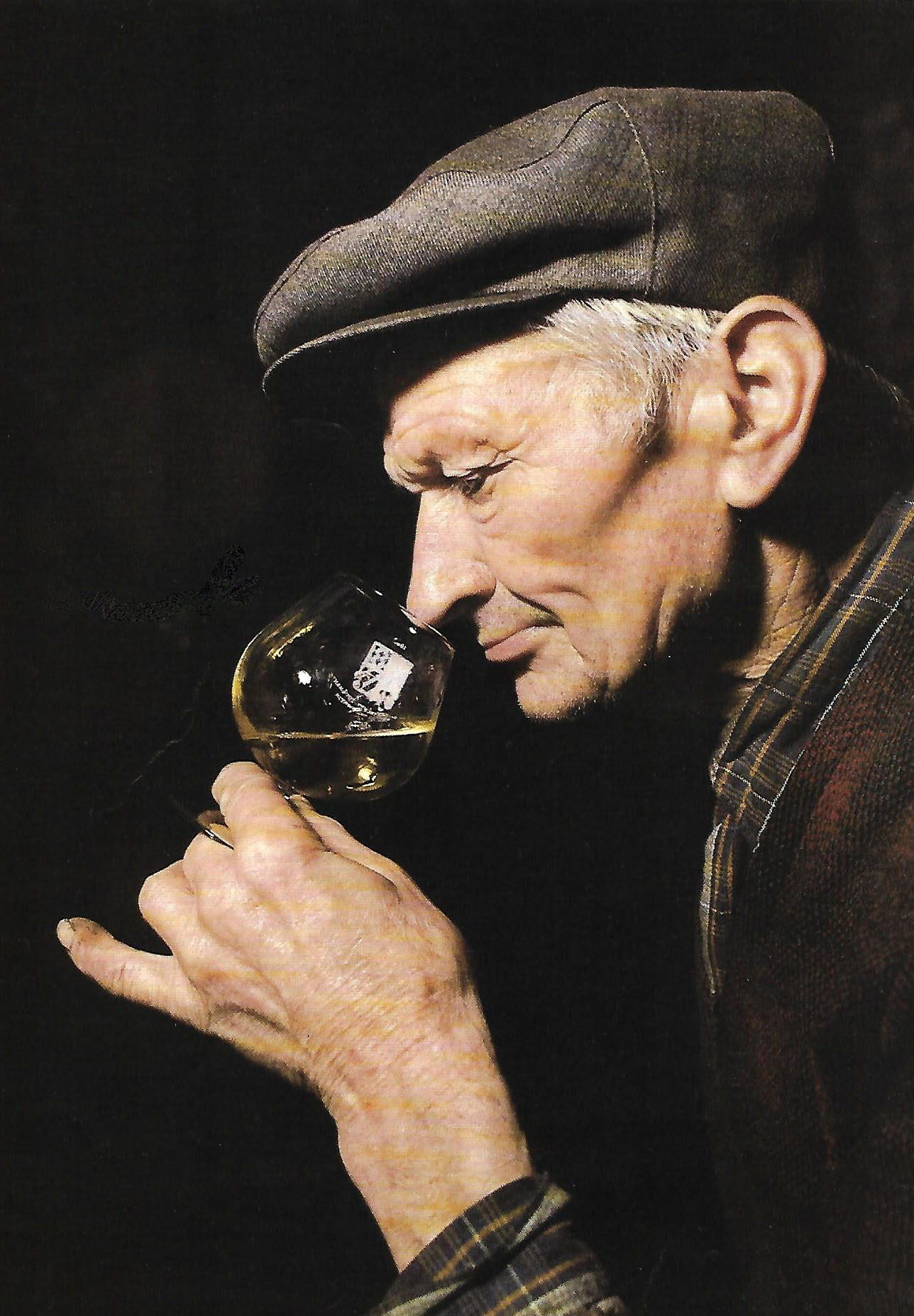

I simply had to pay a visit to the winery, Adega Beira Mar. On arranging an appointment I was delighted to learn that the man who’d given me that bottle a quarter-century ago was still active – and still in charge of the estate. Senhor da Silva, who must be well into his eighties, is full of life and vigour, and gave us a thorough tour of his winery, which doesn’t seem to have changed much over the decades. The wine (only 2,000 bottles a year) is matured in old wooden foudres prior to bottling. One such foudre was from 1886 (the year is inscribed on its front), and others are not much younger.

With a taxi waiting to transport us back to Lisbon (some 40 km away), we only had time to taste one Colares Chitas:

2009 COLARES CHITAS VINHAS VELHAS

An intense blue-purple to the very rim, it gives off a soft maturing nose, of bilberry, liquorice, and violet. The flowery aspect is very pronounced. Soon notes of sloe can be discerned, with a sloe-like acidty giving cut. The wine seems light at this stage, with an ethereal aspect, but will doubltless fill out, as often happens with potentially great wines. The finish at the moment is on the light side, and a bit astringent. Nonetheless, the wine has great presence and needs at least a decade to show its true structure.

As we left, Senhor da Silva gave me a bottle of the 2006, which I was able to taste at the end of the stay, in the charming Gambrinus restaurant, a delightful old-style establishment with an Art Nouveau interior which greatly pleased the eye. That bottle, three years older than the ’09, was absolutely delectable, a wine of great depth and complexity, with a velvety texture and extremely long on the palate. We ended up almost fighting for the last drops.

The aftertaste finished after a few minutes. Yet haunted me throughout the flight home.

© Frank Ward 2019